Taking Your Convention Virtual

This article first ran at gnomestew.com on July 20, 2020.

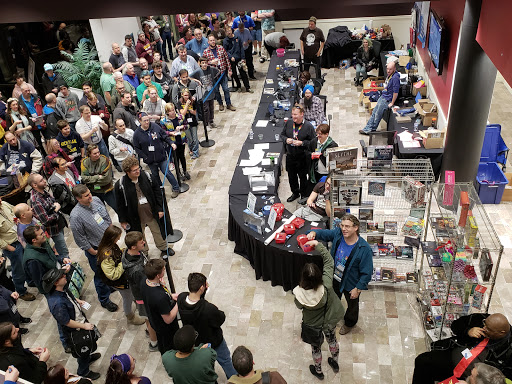

In March, I was organizing what Angela Murray has labeled a “bespoke artisanal convention.” We were thirty friends planning to spend a weekend in April at an inexpensive hotel playing roleplaying games. One month before the con, we determined that because of COVID-19 concerns, it would not be safe, responsible, or legal to hold our small convention as we had planned. Rather than cancel the event, I asked if the participants would like to play online, and that was what we did. We gathered via Discord, Roll20, Zoom, and the like, and collectively played 18 RPG sessions. It was a strange experience to many of them, who had not roleplayed online before. However, the feedback was overwhelmingly positive, with many saying, “I had a great weekend, and I really needed this.”

Because of COVID-19, meat-space conventions are not safe. There, I said it. Reality bites. Getting together at a typical gaming convention won’t be safe for some time. Depending on how the situation evolves, it may not even be legal to hold your convention. Some organizers are trying to fill the void by “going virtual” and holding their conventions online. The local con I support, U-Con, made the decision in July to transition our November convention to virtual.

There are many possible motivations for doing so. Financial and liability issues aside, there are several reasons to host an online convention. The con organization may wish to maintain their brand for when gamers are able to return in person. The opportunity could be used to raise money for a favored cause or charity. Perhaps most importantly, there are large numbers of gamers out there who had their physical cons cancelled. Attending cons is the highlight of the year for many of us. Some of us are probably willing to try out this online thing in order to get the games we are missing.

While online can’t replace a physical convention, it can replicate some of the experiences we seek at conventions: playing games, meeting those with like interests, meeting creators, experiencing geek culture, and shopping for geek stuff. Whatever reason appeals to you, as the organizer of a convention choosing to go virtual, the major task ahead of you is to educate your attendees on how to run and play in online games.

What Games Work Best?

The most common reason people attend conventions is to play games. There are tens of thousands of different games listed on BoardGameGeek, but not all of them are packaged or workable for online play. Let’s take a look at some common game types and see how they can work online.

Roleplaying games translate fairly well to the online format. A theater-of-the-mind style game only requires video conferencing software (discussed later) and your imagination. To add some flair to your game, use screensharing to display digital maps and art; just be sure to keep your gamemaster notes hidden. Online gaming veterans might wish to use virtual table top (VTT) tools like Roll20, MapTool, or Fantasy Grounds for an experience complete with character sheets, digital maps, tokens, and virtual dice. Make sure to practice ahead of the actual game session, though, as these tools are both more complicated to set up and sometimes need tech support to operate.

Board games and miniatures will require specific software to run. There are a wide variety of platforms with various capabilities, some devoted to single games while others have vast board game libraries. The costs vary as well, with many platforms hosting free games, and some platforms requiring a purchase either by one or all participants. Where possible, I strongly recommend that gamemasters choose platforms that are free for players to avoid limiting their audience, but if that is not possible, they should explain requirements and costs in their event descriptions. A few well known services are Board Game Arena, Yucata, Happy Meeple, Tabletopia, and Tabletop Simulator.

A few board games exist which have an open board state, meaning little or no hidden information. This set includes abstract games, such as Go and Chess, but also think basic King of Tokyo. For that type of game, it is possible to run a session with a single copy of the game and a web camera, with players making their decisions verbally. I used this method to run Codenames for friends, sharing a photo of the spymaster card with the spymasters as the only secret information in the game. Before you commit to running a game like this, try it out with friends to see if it’s fun in this format. (YMMV, as King of Tokyo happens to be available on Tabletop Simulator, and you actually get to roll the virtual dice.)

One area where a virtual convention can shine is with seminars and panels. Webinar software is a slight variation on typical video conference software which allows the meeting host to control who is unmuted as well as ensuring that side-chat conversations can be moderated. A Twitch stream is also an option for the savvy content provider. A popular guest or discussion panel can easily support hundreds of viewers. A charity game event or online-party game (e.g. Jackbox) could be live-streamed. A webinar or video stream could also be a great method to allow vendors to offer live demos of their games.

The situation where all players attend from the comfort of their homes may introduce new options rarely seen onsite at gaming conventions. There is a substantial overlap between tabletop gamers and video gamers. Have you ever considered hosting a meetup inside a MMORPG? Maybe you’ll get 5 people, or maybe you’ll get 50. The crafty gamemaster who might organize such an event should consider how the players would be entertained – e.g. going on a certain quest or raiding a particular dungeon.

Meat-space vs Virtual: How Does the Experience Differ?

Running a game online comes with a different set of challenges and requires a different skill set than running a game in person. Each gamemaster should decide what games and platforms they are comfortable with. Depending on the game, your choice of platforms may be limited. Regardless of the technology, gamemasters should practice using these tools ahead of time and be prepared to do some minor troubleshooting with their players. Do NOT try to figure out these tools in the moment. Experienced online gamemasters make it look easy, but it is a skill that is acquired through practice (and learning from misfires).

Most games will require some sort of videoconferencing. Luckily (or perhaps not so luckily), over the past few months many people have become far more familiar and more comfortable with videoconferencing. These tools are widely available and generally easy to use. Google Meet and Discord are free to end users. Zoom, WebEx, and GoToMeeting are also good options, but they require one participant (in our case the gamemaster) to have access to a paid account.

Participants will generally need a low-end computer, internet access, speakers or headphones , and a microphone. The microphone embedded in a laptop can do in a pinch, but a $20-50 headset goes a long way if one has the cash. Using headphones or a headset rather than speakers will also reduce instances of audio feedback. If you are comfortable with it, I also suggest using a web camera to show your shiny face and communicate with gestures (nice ones, hopefully). Visual cues are particularly helpful for indicating who wants to talk and providing clues that a player is distracted or bored. Some game software may require a moderately powered computer to run graphics, so gamemasters should be encouraged to provide (simplified) system requirements to their players at the same time they provide platform and connection information.

As with any form of widely distributed technology, there is going to be someone who has trouble with it. As a convention organizer, you are going to need to decide whose job it is to help your attendees troubleshoot those problems. Is it the individual gamemaster’s job to support their players? Or do you have a dedicated support person available. That is something each con will have to decide. In the case of the 30-person con I described above, we were able to test out audio and video a week ahead of the conference, making the actual weekend a smooth experience for all.

Whatever you choose, it is a good idea to ask for the patience of your players when dealing with their own technology issues and those of others. Disruptions are far more likely than with a face-to-face event. Problems can range from interrupting children (and pets) to lag or disconnection, and software issues could bring the game to a halt. Such interruptions can become very frustrating, and nobody likes having their time wasted. During video conferences, be particularly courteous to your fellow players, try not to interrupt, and use longer pauses when you finish speaking. As with physical games, gamemasters should act as moderators to ensure that everyone is having fun. Remember that we are all there to play games, and it is incumbent upon all participants to make their games a positive experience for all to the extent possible. A little patience with the technology, or your frazzled gamemaster, will go a long way.

How Does Con Differ Functionally?

Some of my favorite in-person conventions support the concept of generic tickets. The idea is that you can sit down at an empty seat and start playing. When the games involve video conferencing links and virtual tabletops, it is not a simple matter to accommodate players who haven’t signed up. While theoretically that could be organized via a Discord server, it’s probably a challenge to manage, and not necessary for a functioning con. It’s a lot easier to manage players when game tickets are reserved ahead of time and video conference and platform information is passed to the players in advance, ideally through your game ticketing system.

There is no question that the online experience is not a perfect replacement for a physical convention. The cost of the attending should reflect that. Remember that attendees and gamemasters might need to purchase software or services just to play some events; they don’t need ticket fees on top of that. A free, cheap, or pay-what-you-want event will earn goodwill from the attendees, who will feel less pressure to make sure their money is well spent. That is doubly true in this economy, where many gamers are between jobs and the games industry itself is hurting. The costs of running a convention online are non-zero, but comparably low, so cover them with a low entry fee if needed. If your organization can afford it, consider donating the rest of your proceeds to a charity or cause. There are many great charities out there, supporting those unable to work with food or cash in this particular time of need. If nothing else, keep your first virtual convention affordable until you work out all the kinks.

A virtual vendor hall is another idea to consider. The game industry is particularly hard hit by the economy. Your game convention typically supports the industry by connecting creators and retailers to customers. A virtual vendor hall would facilitate such connection without the physical presence. Vendors will want a place to show off their wares, possibly directing customers to their regular online storefronts. Gamers will want a means to browse or connect with individual stores. Hosted demo events or streams provide content as well as advertising opportunities. Like many gamers, vendors are hard hit by the economy so, if possible, enable the participation of vendors with free or low-cost options. Provide them with Discord channels, promotional messages, and support for running demos. They will remember when you treat them well, and hopefully support your con in the future.

Any Final Advice?

Online games cannot fully replace the experience of being at a convention. However, through its usage of tools, the virtual convention can provide a means to facilitate meeting friends, old and new. Consider hosting a Discord server for your gamers for a social interaction outlet. Provide them with topic-based chat and video conference rooms, and offer your content-provider groups their own channels. Put events on your schedule specifically for socializing, perhaps late at night or between big events. Make sure such gatherings they are moderated, as any policies about behavior that apply at your physical convention should apply to your virtual convention as well.

We’re all tired of dealing with the plague and its fallout. We all miss seeing our con friends and learning new games. Let’s make the best with what we have and provide a virtual experience. Your challenge is to show your audience that online games are fun, can work, and can give everyone some of the experiences that keep them attending cons. With a little bit of convincing, plus some guidance and support, your loyal followers will be willing to test the virtual waters with you.

Thank you for this insight article.